- Home

- Shirley McKay

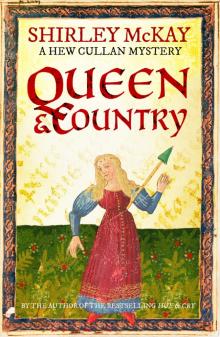

Queen & Country Page 8

Queen & Country Read online

Page 8

She did not call him king, the title she had granted to him while he was alive. Most likely she had never felt it in her heart. But she spoke of Darnley now, in a calm and loving voice. She did not sound like a woman who was troubled in her conscience, or in any way complicit in her husband’s death. She seemed to look back on the years, wistfully detached, as if they were but matters she had come upon in books, memories of things that did not belong to her. ‘That was a handsome young man.’

Hew had answered diplomatically. ‘I cannot say, your Grace, if the king should favour him. I never saw a likeness of his lordship’s face.’

‘We suppose not.’ There was mischief in her eyes. ‘Not all men, after all, turn out like their fathers. And in Lord Darnley’s case, it may not be desirable. But you, we dare say, may yet turn out like yours. You would not be the worse for it.’

‘My father, your Grace?’ He had not, for a moment, thought she would remember him. That was her trick, Phelippes would have said, of pulling people close, of drawing in their spirit and their courage and their confidence, and claiming them as hers.

‘We knew him very well. He should have been our advocate, had times not turned against us. He helped us find our way, when we first came from France. Tell us, is he well?’

Hew had felt blood well up in his ears, like the water that streamed from the fount. He wanted her to stop.

‘He has been dead for three years, your Grace.’

‘Then we are sorry for it. That was a good, loving friend. And a good Catholic too. Did he build his house, on the land we gifted him?’

‘What land was that?’, he could not help but ask, and did not want to hear.

‘It was land that had belonged to the archbishops of St Andrews, and had come into our hands. He would not have a title, or a place at court, but asked for leave to live out quiet in retirement; since that land had come to us, and was of little worth, we placed it in his hands, a small mark of our gratitude. Now, as we suppose, it must be yours. Did he not say?’ she had asked, in her eyes a faint flicker of hurt. ‘We suppose he did not, for it was not much.’

He had answered her, hollow, it was the world.

At Chartley, Phelippes said, ‘I do not blame you, Hew. For your duty to my family, I must give you thanks. But the truth is you have come here at an awkward time. Your appearance has thrown Amias in a heightened state of fear. He does not dissemble well, and in his agitation may resort to such a rigour as will make the Scottish captive fearful for her life, which is not what we want, for we must console her with a smiling countenance, and keep her mind and spirit free from all suspicion. I can hope to still Amias, and make calm his fears, but until this work is done, I must keep you here. I am sorry for it, but I cannot let you go.’

‘Then your family,’ Hew objected, ‘will despair of us both.’ He had no wish to be kept as a prisoner at Chartley.

‘I have written in the letter that you will remain here, to help me with my work, that we may the both of us more speedily return. Laurence will see that it finds its way to Mary, and that your coming here will not be known to Walsingham, until we have undone whatever harm it caused. He will hear it soon enough, and he will not be pleased. You have been irksome to him, from the very first. You must be aware, there is a net about to close, and I cannot run the risk of your warning the conspirators.’

‘How should I warn them?’ asked Hew, ‘when I do not know who, or what they are? You know, upon my life, that I will take no part in a conspiracy, against either queen.’

‘Trust me, when I say, we know that all too well. Therein lies the trouble, Hew.’ Tom sighed. ‘We do not want, besides, a second thief to fly.’

He was alluding to the fraud Hew had uncovered in the custom house. ‘That is not fair,’ Hew objected. ‘The thief was alerted by the presence of a stranger. He would loup at a shadow. He was poised for flight.’

So much had been true. Yet when he thought of the face of that foolish young piker, nervous as a lute-string, no more than a boy, he could not have sworn he would not have forewarned him, had the frightened faulter given him the chance. He had not had the stomach for the taking of a thief. His heart was harder now.

‘So much may be true of the conspirators. And if they were to fly, and you go out from here, what conclusion, think you, Walsingham would take from that? No matter if he knew you had no hand in it, you would pay the price. He would make you suffer for it. It is vexing to him, that he cannot put your talents to their best effect. Your conscience is a trial, and cannot help us here. Wherefore, you must stay, and we must watch and wait, till Walsingham sends word.’

Chapter 7

A Dead Man in Delft

Phelippes kept him close, for Hew’s sake and his own. He hoped that Hew had good intentions, yet he could not take that risk. For though he knew him well, could capture to the life the manner of his speech, the letters from his hand, and frame them in a wink, he could not win his confidence, or see into his heart, as Laurence Tomson did.

Hew had never spoken with, or seen, that queen again. His journey to the spa had been judged successful. Phelippes had informed him that Walsingham was pleased with him. ‘It is better than we hoped. She liked you. So much, in fact, that she has asked the earl for you to be enlisted in the service of her household. She says’ – and he had smiled at this – ‘that she wants a Scottish man of law, having for the present only someone French, and that a friend had told her, you were close at hand. The pity of it is, it cannot be agreed, for she cannot be allowed to think that she can have her way, nor to become suspicious of her will acceded easily. But, you can be attached to the household of whoever has the keeping of her when the earl demits it, the better to insinuate, and build upon her trust.’

It was rare enough that Phelippes showed his hand. Doubtless, it had been his own idea, to try Hew in that place, and he had been well satisfied, at first, with the result; that queen was taken in. The sticking place had been their confidence in Hew, who could not be trusted not to play a double game.

Hew had spilled his heart to Laurence Tomson, knowing as he did so it would go to Walsingham, that Laurence, in all conscience, could not recommend him.

‘He is honest, in all ways, to his faith and country, that is to say, to his king. And where there is no conflict with his own beliefs, so far, we can trust him. He will not, I think collude in any manner of conspiracy, that threatens to unseat the Scottish king. There is no question of his faith. He could no sooner change it than the colour of his eyes. It is thorough and complete. But his quest for justice, of a personal kind, sometimes supersedes his allegiance to the state. He has confessed that he was moved by the appearance of that queen. That queen has a claim over him, through family ties, not easily thrown off. He will help us bring her down, if he sees her harm to us, yet may not be persuaded to it by whatever means; he will not see that the method may be justified by cause, and where it is our will her malice may betray itself, he may seek to mend, or put her on her guard,’ Laurence might have said.

‘She knew his father. Is that all?’ Phelippes put contemptuously.

Laurence understood that it was enough.

Laurence had recommended Hew have nothing more to do with the queen of Scots, less likely in that cause to help them than to hinder it. ‘What devil shall I do with him?’ Walsingham asked then. His answer came emphatically, more bloody and more urgent, than he did expect.

It was Phelippes who had brought the news to the house at Leadenhall, not long after their return from Buxton spa. Aroused by the commotion, in smocks and linen caps, the older family members had been shaken from their beds. Hew had been going out, to see if Audrey would be willing to indulge in conversation on a sultry summer’s night, while Frances sat alone, in solitary candlelight, transcribing for her uncle the accounts of business done by Phelippes and his brothers in his absence at the baths.

William, the Silent, of Orange-Nassau, stadholder in the Netherlands, was dead, shot through the stomach in hi

s dining room at Delft. Phelippes had resounded every lasting note, harrowing and pitiless. The assassin had bought the weapon he had used with money that the stadholder had given him himself, to buy a pair of shoes; a penniless fanatic, he had nothing in his pockets but the bladder of a pig – to keep himself afloat as he swam through the canals. With hopeless satisfaction, Phelippes had described the bodily afflictions that were practised on the perpetrator in the hours of anguish that were drawn out till his last, sparing no account, until his mother’s shuddering and murmurs of disgust, and Frances’ pale face, caused Hew to protest that this was not the place.

‘Not the place?’ Phelippes cried. ‘You will say tis not the place, when we are overrun, and all that we hold dear is brought down in flames. There is not a woman nor a child would shrink to see sharp justice pinch and sear his flesh, and trail the flaming ribbons smarting through the crowd. Anyone who whimpered at it, would be flayed alive. And rightly so.’

Joan had whispered, Tom, and William had objected that the women did not like to hear speak of such things, so tender were their hearts.

‘Then better they had learn to make them hard, against the terror that will strike them, that threatens all the world.’ And brought to a standstill by a savage kind of grief, a fury wrought of impotence, the staid Thomas Phelippes, who had seemed impassible, had broken down in tears.

Though Hew had not wept, the cold grip of horror had clutched at his bowels, and left him sick at heart. The loss of that good prince had touched him in a personal way, over and above the damage it had done to what was right and civil in the Christian world. He had met the prince in 1582, on travels in the Netherlands, where William had been kind enough to treat to save his life, when Hew had found himself in hostile Spanish hands. The prince had been disfigured from a gunshot wound, and Hew had learned of courage, moderation, love, in the gentle contours of that ravaged face. So resolute a Calvinist, he would not take precautions to protect his life, nor close his gates and mind to those who meant him harm, for what would be, would be; and so, of course, it was.

Once Phelippes had departed, and the house was still again, and Hew was drawn at last into a restless sleep – no more thought of Audrey – he had dreamt of that face, and felt upon his head the light touch of the blessing of that gentle prince. The hot-water bladders of the spa at Buxton were blown up into water wings, a fool’s bladder bobbing on a Dutch canal, that became the swollen belly of a man upon a stick, spilling out its innards like a pudding in a flame. Hew had woken to a world that felt bleak and desolate, that no amount of rage, no spilling out of blood, could possibly assuage, a tidal wave of terror that had caught him in its flood.

That day, or the next, he was called to Seething Lane. It was clear to him that Laurence Tomson had not slept for days. It fell to Laurence to receive most of the correspondence from the Netherlands and France. Hew wondered whether he had had the task of breaking the news to Walsingham, which Walsingham himself had broken to the queen. There he saw letters from the embassy in France, warning that Elizabeth was now in mortal danger; he could only imagine the fresh flux of fear the news would discharge on the Scottish king James.

Walsingham was there, shivering in furs despite the summer heat, and seemed to shrink inside himself. His voice was hoarse and rasping, and he barely looked at Hew. He delivered his instruction, with a cold, distracted air. Hew was to take a paper, which Laurence had prepared for him, to the gaol at Newgate. Hew had felt quite sure the paper was the warrant for his own arrest. But Laurence, in his quiet way, had set his mind at peace. ‘Take the letter, and this purse, to the keeper of the upper floor. He is a scoundrel, and will ask for more. When you have what we want, come back.’

Hew had asked, ‘What is it that you want?’

Laurence had allowed the slightest twitching of a lip, too worn out to smile. ‘To see my wife and daughter, and a good night’s rest. Take courage, Hew, and heart. You will like what you find.’

Hew could not imagine what he could have found to please him in Newgate, a place that even Phelippes sidestepped, from a kind of superstition, when he showed to him the town, that had as many depths to it, as were sorts of men. It was unlikely such a place, where a seeping rot corroded every joint and sinew, should not infect the man who had the keeping of it, however well-intentioned he might once have been, and the keeper Hew had met was tainted with corruption long before he came. He had taken up the purse and turned it in his hand, and answered true to form, that it was not enough.

‘For thy miching sclaunder, it is recompense. By order,’ Hew had said, ‘of the queen’s ain secretaire.’

The man had scratched his head, baffled at the Scots, which Hew had delivered with an open countenance, keeping his face straight.

‘This villain is a loose one. He is violent, see? This is little solace, for the trouble he has caused.’

‘Then you will be thankful to see the back of him,’ Hew had told him cheerfully. ‘Else you will account to Mr Secretary Walsingham, fetch him up at once.’

Privately, he wondered what kind of a monster he had to recall up from Hell itself. The gaoler spat upon the floor, a slick gobbet of disgust. ‘A bastard he is, like yourself. That is to say, a Scot.’

He had left Hew at the gate, returning in a while with a creature caked in filth, shaking out his limbs a little in the welcome air. The prisoner flexed his knuckles, which were bruised and bloodied. ‘Well met, my auld friend.’

Hew had gaped at him. ‘Robert Lachlan, can it be?’

Robert had answered with ‘Whisht,’ and pulled him out of earshot of the jealous guard. ‘I could dae wi’ a drink.’

‘And a wash.’

‘Now whit wad a man want wi’ that? The pity is, there isnae time. We maun gang awa an play court tae your man.’

‘But how did you end up in Newgate? What have you done?’

Robert had answered, his job.

Lachlan was a man for hire Hew had first met in Campvere. He had seen him last in St Andrews harbour, setting sail for Ghent.

‘You did not tell me,’ he accused, ‘that you worked for Walsingham.’

Robert Lachlan shrugged. ‘I telt you that I wasna working for Sir Andro Wood. And that is the truth. If they were in league togither, what was that to me? I never liked that man. But Walsingham, I serve fae time to time.’

He had been in Newgate, not for any crime, but to lie among the Catholics there, reporting on their plots. It was a role to which he had adapted naturally; in the Spanish wars, he had fought upon both sides, no more and no less than a man for hire. Most of the soldiers there were ordinary mercenaries, who bore little malice to the other side, and there was small distinction on the battlefield. Most of the fighters, on whichever side they fought, had admired the prince of Orange. Robert had the fortune to be entered in his service, earning his respect, and on one occasion, saving his life. He took it amiss that the life he had saved had been snatched while his own back was turned. When one of the papists in Newgate rejoiced at it, Robert had broken the vaunting man’s face, and had had to be pulled from his quivering carcass. His shirt sleeves were stiff with the blood, and with it his cover was blown.

Walsingham was furious. ‘Four months. Four months to win their confidence, and you give it all up. What those men might hide, we may never know.’

Robert said impassively, ‘They had nothing to hide. Or I had found it out. You can hang them now.’

‘Hang them, for what? Four months you had, and ran up exorbitant bills, for meat and strong drink.’

‘The drink was to loosen their tongues.’

‘And, when it did, you stopped them at once. God help you, man, I thought you could control yourself.’

‘No man could control himself that was so sore provoked. Twas slander to the finest prince that lived,’ Robert had declared.

Walsingham had snapped, ‘Do not, I warn you, show such strong allegiances, that they amount to treason. Since you feel so strong, you will thank me for the c

hance to avenge that prince’s death, and not be left to rot in the dungeon you deserve. Tis likely that her Majesty will wish to act on this, and send some fighting men. You two shall go ahead, as far south as you can, and send us back intelligence. For you were there before, and served well in that place. God knows, I see no other hope for you.’

‘I am not a soldier,’ Hew had reminded him.

‘And he is not a wit. Yet between the two of you, you may make a man.’

Audrey had a bloody streak. She liked to watch the puppet shows at Tyburn and Tower Hill, to catch wind of a scent that even Phelippes shrank from, wafting from the walls of Newgate and the Fleet. Audrey would not flinch, to see a man’s flesh torn, nor shudder at his cries, ‘if that man deserved it’. And yet she was not cruel. She pitied the poor fool, and would give a crust to any honest beggar she saw passing by. At the fair, she had wept, at a bear kept in chains. ‘I am that tender at heart. It is not just, do you see?’ she explained it to Hew, in the warmth of her bed. ‘That poor bear had done nothing wrong.’

He lay with her all night, the night before he sailed, breathing in her perfume, pungent, rich and dark, closeted inside the whiteness of her flesh, pillowy and ponderous. Her plump fingers tickled the scar on his chest, counting the holes that the needle had made. When her husband had been killed, a knife had pieced his throat. ‘No more than a prick. But you would not believe, how much there was of blood. His beard was like a brush with it, bristled stiff and black.’

He felt her weight upon him, and yielding to the warmth, the comfort of her thighs, he found himself more spent than sated, lunging into emptiness. ‘Be sure and come right back,’ she said.

And he had understood, that if he did return, it would not be to her.

Their ship had set sail at first light, and as they waited at the dock for the lighters to set out, Frances had appeared, with a bundle for them both, of blankets, beef and cheese, and a flask of beer. Hew had been moved by the sort of kindness that his sister would have shown. Frances had touched him, briefly on the cheek, and her touch was light and cool. ‘I wish you to be careful, Hew. The stories that are told . . . I could not bear it if such cruelty should be done to you.’

Lammas

Lammas Candlemas

Candlemas Hue and Cry

Hue and Cry Martinmas

Martinmas Fate and Fortune

Fate and Fortune 1588 A Calendar of Crime

1588 A Calendar of Crime Time and Tide

Time and Tide Friend & Foe

Friend & Foe Queen & Country

Queen & Country