- Home

- Shirley McKay

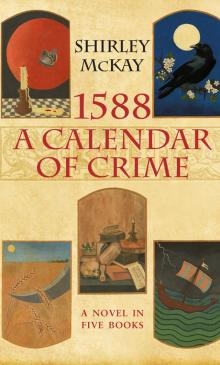

1588 A Calendar of Crime

1588 A Calendar of Crime Read online

1588

A CALENDAR

of CRIME

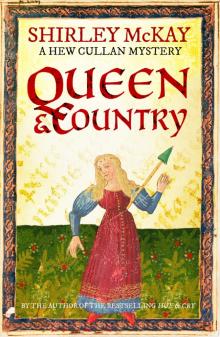

By the same author

HEW CULLAN MYSTERIES

Hue & Cry

Fate & Fortune

Time & Tide

Friend & Foe

Queen & Country

This edition published in Great Britain in 2016 by

Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.polygonbooks.co.uk

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN 978 1 84697 363 5

eISBN 978 0 85790 911 4

Copyright © Shirley McKay, 2016

Illustrations and calligraphy © Cathy Stables, 2016

The five individual books in this novel are published separately as eBooks

The right of Shirley McKay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

Text design by Studio Monachino

Printed and bound by Scandbook AB, Falun, Sweden

Endpapers: Calendar, Monogrammist HK (engraver), Rijksmuseum, The Netherlands. Page 298: From Jost Amman’s Stände und Handwerker mit Versen von Han Sachs (1884), Wellcome Library, London.

CONTENTS

BOOK I

Candlemas

BOOK II

Whitsunday

BOOK III

Lammas

BOOK IV

Martinmas

BOOK V

Yule

1588: FOREVER AND A DAY

A LIFE SHAPED BY SEASONS: HISTORICAL NOTES

GLOSSARY

BOOK I

Now diverse secret agues breed

Be choice of food, beware of cold:

Abstain from milk, no vein let bleed

In taking medicines be not bold

RICHARD GRAFTON’S ALMANACK,

A brief treatise, conteinyng many proper tables and easie rules… (1571–1611)

I

The candlemaker’s boy was thankful for the moon. Without its friendly glare, he would have to make his way through darkness down the path adjacent to the cliff, perilous by day, let alone at night. And no one but a lunatic would care to take that chance.

A crowd of yellow pinpricks clustered at the Swallowgate, where lanterns cast a dimly well-intentioned light, but over to the west the darkness pooled and chasmed, blacking out the cliff top and the gulf beyond. And westward was the crackling house, set back from the town, where the salt winds might snatch the rank air, and the sea water carry it off.

In the year of plague, the dead had been laid down to rest in this place. So much that was noxious was settled in the wind. The candlemaker’s boy muttered out a prayer, and shuddered as he passed. He thanked God when he came upon the low flame of the crackling house, swinging at the door as the law required. A slender skelp of taper guttered in the draught; the candlemaker grudged to spare the smallest light.

The boy entered the crackling house, pulling off his hat. ‘I have done what you asked.’

The candlemaker, bent over his great greasy pot, did not look up. ‘Is that a fact?’

‘I went to a’ they houses, all the ones you said. The auld wife at the last one wasnae best pleased. She wis not pleased at all.’

‘No? And why was that?’

‘She said ye had not sent her all that she had asked for. And she did not like the candles that you sent. She said that the tallow was filled full o cack.’

‘That guid wife is a lady. She did not say that.’

‘No. She said – ’ the candlemaker’s boy assumed a high-pitched plaintive voice, pinching at his nose, ‘Please to tell your master, there is offal in it. Oh, but it does stink!’

‘You do the lady wrong, to mock at her like that,’ the candlemaker warned.

‘She is not so gentle, as you seem to think. She says she will not pay you the prices you demand. She says you have extortioned her. She says she will report on it to the burgh magistrates.’

‘She will not do that. And she will pay the price. For we ken what it is that she does with her candles.’

‘Do we?’ the boy asked, unsure.

‘Of course we do, you loun. What did she gie to you, to thank you for your pains?’

‘Nothing. I telt you, she wasnae pleased.’ The boy stamped his feet. ‘Three miles through the dark, and the wind was fierce.’ He did not tell the fear, the horror he had felt, to shiver in the great hall of that wifie’s house, where, he was quite certain, there had been a ghost.

‘Cold are ye? Come by the fire.’

‘Nah, I’m a’right.’

‘Did you no hear me, son? Come by the fire.’ The candlemaker left his post to slide a helping hand around his servant’s shoulder. He grasped the boy’s ear, and twisted it sharply. The boy gave a yelp. ‘Whit was that for?’

‘What did she gie ye, ye wee sack of shite?’

‘Nothing. I telt you,’ the prentice boy whimpered, wrenched by his ear to the rim of the pot. ‘For pity, you will hae ma lug off.’

‘Aye, and I might.’ The candlemaker let go of the ear, that was throbbing fiercely, radiant and red, but before the boy could cup it in a cooling hand he felt the candlemaker’s fingers strangled in his hair, forcing him down to the filth of the bath.

‘Mammie!’ He could say no more, for the fumes from the tallow filled his eyes and lungs, and his legs beneath him buckled at the stench. A little of his forelock flopped into the fat, and began to stiffen as his master pulled him up. ‘Why wad ye do that?’ he wailed.

‘For that you are a liar, and an idle sot.’

‘I did not lie. She gied me naught. I telt you. She was cross.’ The boy was snivelling now. Perhaps it was the fumes. He could not help the streaming from his nose and eyes. He ought to be inured to them. He ought to be inured to the candlemaker’s wrath. It was not the force of the fury that disarmed him, and caught him off his guard – fearful though it was – it was that the moment for it could not be foretold. The candlemaker’s boy could seldom see it coming; he had not that kind of wit. And, when it came, it knocked him from his feet.

‘Mebbe that is true,’ the candlemaker said, and the boy felt his nerves shiver to a twang, ‘but that does not excuse your fault in your craft. What do you say to this?’ From their place upon the rack he pulled down a rod of limp tallow candles, all of them shrunken and spoiled. ‘What do you say?’

‘They were too early dipped.’

‘And what limmar dipped them?’

It struck the boy, quite forcefully, that it had not been him. Perhaps it had been the candlemaker’s wife. He gathered to his service what he had of wits, and managed not to say so. ‘Ah dinna ken,’ was what he spluttered out.

‘You do not ken?’ The candlemaker raised his arm, and paused, to rub at it.

The candlemaker’s boy took courage from the pause. ‘I heard the surgeon say, ye must not strain yourself.’

‘Not strain mysel’?’ The candlemaker glowered, and let his sore arm drop. ‘I’ll show you strain.’ But something in him slackened, and appeared to slip.

‘Will I do the work again?’ the boy suggested then.

‘I’ll see to it mysel’. You will pay for the waste, out of your wages. Awa with you, now. Hame

to your lass. Look at ye blubber. Ye greet like a bairn.’

The candlemaker’s boy rubbed his nose on his sleeve. ‘Ah dinna greet.’

It was the odour of the grease pot that had caused his eyes to stream. Surely it was that. He could feel the tallow drying in his hair, the tufted strands of sheep fat pricking up on end. His master could see it, and his humour changed. ‘Tell your lassie I have dipped for her a scunner of a candle. She may put her flame to it, if she can stand the stink.’

The boy’s wit as always was slow to ignite. ‘Whit candle is that?’

‘You, you lubber, you.’

It was not for kindness, nor from common charity, that he sent the lad away. Charity would be to give the boy a light. Instead, he let him flounder, on the dark path home. And if the candlemaker stayed to work on through the night, in spite of his sore arm, then he had a purpose for it that was all his own. There were certain kinds of business played out in the darkness, and best prospered there; business of that sort had no business with the boy.

At nine of the clock, or a little before, a visitor came. He had brought with him his own little lantern, in a sliver of parchment, like the ones the small boys bound up on to sticks, to carry back from school on winter afternoons. The candlemaker thought it would not last the wind, to see the bearer home.

The visitor was well wrapped up. Perhaps against the wind; perhaps against the flavour of the candlemaker’s shop – the crackling had a savour not to everybody’s taste; perhaps because he did not wish to show the world his face. He wore a kind of cowl, a long and shapeless gown, a hood up round his head. His muffler could not mask the feeling in his eyes, which were pale and agitated. He looked about, and back, as though the shadows of the night might engulf him on his way. His words, when he spoke, were low and unwilling. ‘So. I have come. As you said.’

The candlemaker lifted out a row of candles from the pot. He stood awhile, considering. Then he placed them carefully to dry upon the rack, and took up another row, preparing them to dip. ‘A moment, if you will.’

‘Yes.’ The visitor accepted, and remained politely, while the row was dipped. It was not until a third descended his impatience showed itself. ‘I cannot stay so long. If you do not have what I want —.’

The candlemaker showed no flicker of concern. ‘I have what you want. But this is a business that cannot be rushed. If it is rushed, it will spoil, do you see?’

‘I see that.’ The visitor was courteous, conciliatory, even. The candlemaker sensed that he would not put up a fight. ‘But, I think you said to be here before nine. And it is nine now.’

To confirm this, the St Salvator’s clock at that moment could be heard to strike the hour.

‘I believe, sir, it was you that fixed upon the time,’ the candlemaker said.

The visitor conceded, ‘Ah, perhaps it was. My pardon to you, sir. But since you are still occupied, and I may not stay long, I shall come again. Tomorrow, if you will.’

The candlemaker smiled. ‘Aye, just as you like. Though I must warn you, sir, that I cannot promise I will have tomorrow all that ye require.’

‘But surely… since you say you have it now…’ The visitor, plainly, was baffled by this.

‘I have it for ye now. And, sir, I have kept it for you, at some trouble to myself, when the commodity you look for is very dear and scarce. If you will not take it now, I cannot be expected to have it still the morn.’

‘But I will take it now, if you will only give it to me!’ the visitor exclaimed.

‘Very good. I will. When the rack is done.’ And the candlemaker, blandly, went on with his work.

The candlemaker dipped, for such a length of time as he could see the patience of his customer last out; he judged it very fine, like the grains of sand running through a glass; and when he saw that the great mass of sand, all in a rush, was about to flood out, he straightened up quickly, and said, ‘If you will take it now, sir, I will fetch the stuff.’ And from a shelf in the shop, where it opened to the street, he produced a slender box. This he opened up. ‘Fine, is it not?’

‘It is less substantial than I had supposed. That is, for the price…’

‘As to that,’ the candlemaker intercepted smoothly, ‘it comes in at two pounds, six shillings and sixpence. And, I suppose, you would also like the box. A shilling for the box and the paper in it. I will not count a penny for the scrap of string.’

The visitor blinked at him. ‘Two Scots pounds, we said.’

‘So much had I hoped for. I do not set the price. And, as I have said, it was hard to find. But the profit to you is, I ask nor answer questions. Whatever you will do with it, is your own affair.’

‘I understand you, sir. The pity of it is, I cannot pay that much,’ the visitor confessed. ‘This is all I have.’ And, to prove his point, he emptied out his purse.

The candlemaker hesitated. ‘I do not always do this. But, as I believe, you have an honest face’ – so little of that face as was left to view. ‘Give me the two pounds. And you can owe the rest. Can you write your name? Then put it in this book.’ He took out from the counter a fat leather notebook, and opened to a page, on which the date was written: First of Feberwerrie. ‘That makes, in all, seven shillings and sixpence.’

The visitor glanced at the book. He squinted at the figures. But he did not seem convinced. ‘Seven and sixpence? What are your terms?’

‘Pay the money on account by the first of March, and the debt will be cleared, without further cost. If you cannot pay, interest will accrue, but we need not speak of that until the debt is due. Sign for it now, this very day, and you may have the stuff to take away with you. Or, if you will not, I must offer it for sale.’

The visitor agreed. He signed his name and left, the burden of his dealings bundled in his cloak. He fled the crackling house, as though the devil’s spur and pitchfork pricked behind him. He did not look back. And the candlemaker’s prophecy was proven to be right, for his sliver of a lantern did not last the wind.

The candlemaker meanwhile worked on through the night. Though he had made a profit he did not feel quite satisfied. He felt a deeper sense that something was not right. And he did not feel well. His legs were weak and tired. His forehead and his forearm had both begun to throb. The bandage on his arm was bulging, hot and tight. He sat down in his chair and loosened it a little, letting out the cord. He let his dull eyes close, and soon he was asleep, so shuttered to the world, he did not hear the latch.

Frances had not slept. For a while she shifted, soundlessly sought rest, before she slipped the shackles of the heavy quilt and found solace in the shadows by the window sill. Hew felt the coolness of her absence in the bed, and woke to find her gazing out upon the moon. ‘Is there aught amiss?’

‘Nothing is amiss.’

‘Will you come to bed?’ He felt for the tinder box, striking a flame. Frances said, ‘Don’t.’

Bewilderment clutched at him still. ‘Do not light the candle,’ Frances said. ‘So little have we left, of the purest wax. Bella says tis hard to come by, at this time of year.’

‘Tomorrow, I will fetch you some.’

‘I would not have you trouble, for my own indulgence.’

‘It is not indulgence. You shall have the best.’

Frances had developed an aversion to tallow, in candles of the common sort, as to the scent of flesh, and fat of any kind. It was parcel of a change in her that mystified and baffled Hew, though his sister Meg assured him it should not be feared. He had done what he could to keep her in comfort, over the last seven months. Now the store of beeswax, apparently exhausted, caused him some concern. The cost of the candle meant little to him; yet scarceness was a thing he could not help but count. The town trade in wax had been stifled at the plague, where the sweet balm of the wax-maker’s craft had conspired, drop by drop, to draw him to his death.

‘Besides,’ Frances said, ‘there is light enough. Tomorrow night, I doubt, the moon will be quite full.’

The

re was truth in that. At this time of year, on a cloudless night, there was more light to be had in the glancing of the moon than in the laggard day, when the sun struggled blearily across the sullen sky. So it seemed to Hew, as he rode out in the blinking of a bloodshot dawn, to fulfil his obligations at the university.

The porter at St Salvator’s hailed him at the gate. ‘Good day to you, professor. Doctor Locke is called out, urgent, to a casualty. He asks if you can read for him his early morning lecture, on the chiels, an such.’

De caelo et mundo, Hew interpreted. ‘Certainly I could. He did not, I suppose, report the nature of the accident?’

‘Only that it was a most woeful and perplexing one.’

Casualty, Hew thought, was a curious word, and no doubt one the porter had not thought up by himself. Hew’s closest friend, Giles Locke, was Visitor for Fife, reporting to the Crown on unexpected deaths. Hew was accustomed often to assist him, and, in legal cases, to assume the lead. Where there was a casualty he felt an interest too, and a little piqued to be left behind.

‘He will be obliged to you. For he was afeart the students will revolt, and take it for a holiday. They may not have a holiday, though they will entreat for one, on account of Candlemas.’

The old tradition was, in grammar schools at Candlemas, the scholars gave their masters silver as a gift to fund the cost of lighting in the schoolroom for the year. The schoolmaster would grant them a play day in return. And college students hankered still for such small indulgences.

‘The wind is, we shall have a royal visitation, in the Whitsun term. Wherefore, says the doctor, keep them to their books. And the student Johannes Blick is keen to speak with you,’ the porter went on.

Hew smiled at that. ‘No danger, I suppose, that he is pleading for a holiday?’

‘None at all, I fear.’

Johannes was the son of a Flemish merchant, in his final year. In age in advance of his fellow magistrands by a year or two, he outstripped them by a score in intellect and aptitude. And there was no doubt, when the king’s commissioners came to make their inspection, Johannes would stand out among them as a shining star. Yet day to day, his brightness was a strain. When his tutor could not fathom to the bottom of his questions, he had turned his attentions devotedly to Hew, an attachment which occasioned as much mirth among the college, as it did relief. Hew had done his best. He had lent him books, and given many hours to hearing out his arguments. He liked Johannes well. Yet still there were days when he would sigh and sink to hear the fatal words, If I might for a moment, sir, intrude upon your time. Then time would run like sand, and never be enough.

Lammas

Lammas Candlemas

Candlemas Hue and Cry

Hue and Cry Martinmas

Martinmas Fate and Fortune

Fate and Fortune 1588 A Calendar of Crime

1588 A Calendar of Crime Time and Tide

Time and Tide Friend & Foe

Friend & Foe Queen & Country

Queen & Country