- Home

- Shirley McKay

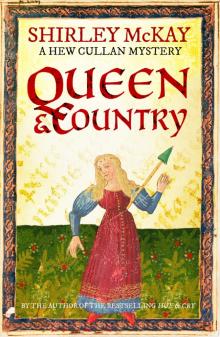

Queen & Country

Queen & Country Read online

Queen & Country

Other titles in the Hew Cullan Mystery series

Hue & Cry

Fate & Fortune

Time & Tide

Friend & Foe

This edition published in Great Britain in 2015 by

Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.polygonbooks.co.uk

ISBN 978 1 84697 312 3

eISBN 978 0 85790 852 0

Copyright © Shirley McKay, 2015

The right of Shirley McKay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

The publisher acknowledges investment from Creative Scotland towards the publication of this volume.

Typeset by 3btype.com

Contents

Prologue: St Andrews, November 1586

Part I

Chapter 1: The Queen’s Highway

Chapter 2: Leadenhall

Chapter 3: A Quiet Man

Chapter 4: Chartley

Chapter 5: The Lion and the Hare

Chapter 6: La Reine Marie

Chapter 7: A Dead Man in Delft

Chapter 8: Frost of Cares

Part II

Chapter 9: The Opened Bud

Chapter 10: Ars et Natura

Chapter 11: An Efficient Cause

Chapter 12: Ash Wednesday

Chapter 13: The Touchstone

Chapter 14: Peregrines

Chapter 15: The Lion’s Den

Chapter 16: Perspectives

Chapter 17: Painters’ Colours

Chapter 18: Memento Mori

Chapter 19: Speaking Pictures

Chapter 20: The Doctrine of Signatures

Chapter 21: A Devil Incarnate

Chapter 22: Letters Home

Chapter 23: Queen and Country

Notes and Attributions

Historical Figures

Glossary

Prologue

St Andrews, November 1586

The pedlar came to Scotland once or twice a year: in springtime when the leaves were opening in their buds, and sometimes when they fell, before the way was bared and bound in winter frost. In the year of the plague – a bad year that was – he did not come at all. In the course of a good year he crossed from his home in the midlands of England its length and its breadth, and then up north and down again. He brought his haberdashery to manor, fair and farm. He was welcomed in the houses landward of the towns, for his toys and baubles and his scraps of news, where news was slow to reach. In the burgh markets, he was made less welcome, and those he came to only for the annual fairs, when he would pitch his stall, and voice, among the rest.

This year, it was not until September that he crossed the Scottish border, to return to his old ground on the well-worn cadgers’ paths. Here, he was assured to find a rousing cheer, comfort, meat and drink. He knew that his customers, after months of plague, would be glad to see him. The pack upon his back was as heavy as himself, lumbered with delights, when he first set off.

And yet, and yet, he did not find a welcome there, but a shifting silence that he could not comprehend. Wherever he went he was met with mistrust. Coming to each town, where he was turned out, he expected the good wives to follow him in droves and cry to see his wares; that did not happen now. And when he wandered landward to the little cots, expecting warmth and cheer, he found their doors were closed to him. In vain, he waved his paper proving he was hale, and free from pestilence. He could not understand it. Starved as they had been, had their hopes and wants withered in the plague?

For once, he was behindhand with the news. The news had swept before him, like a line of fire that shrivelled to a husk all in its path, so that his trudge was through desolate landscapes, all solace closed to him. The news had gone before, closing every port, and darkening every brow that once had offered friendship. And no one thought to tell the pedlar what it was.

He came at last, at the end of November, to the South Street of St Andrews, for the last of the fairs before winter came, St Andrew’s Day itself. The people here he knew would be flocking to its stalls, flocking for the first time in a full year since the plague, looking to stock up not simply on commodities, but on a mirth and lightness now in short supply. And if the crowds were depleted, and a little more subdued, than the last time he was here, the pedlar’s spirits still were high that he would find a market for his buttons and his beads, his crudely painted soldiers and babies wrought of lead, his rattles and his pins. There were people enough, craftsmen and labourers mellow in drink, students and schoolboys truant from schools, good wives and masters in holiday clothes. There were scholars also, from the university, who wanted books and paper, sealing wax and ink. The pedlar would have liked to purchase those things too, to carry back down south, but until he offloaded the goods he had brought, he had no hope of that. The merchants had forestalled, picking off the cream that came from overseas before it left the ships. He saw the town apothecary, filling up a sack with spice and painters’ colours, long before the man who brought them from the Orient had opened up his stall.

Yet he was not deterred, for in a restless horde, that hankered after novelty, there was room for all; and if he could not hope to have a prime spot for his stand, he had the advantage that he could slip among the crowd, nimble as a pick-purse, to ply his stock-in-trade.

The town drummer and piper had set up their roll, and the swelling of a crowd, with ale in their bellies and money in their pockets, encouraged the pedlar to stake out his claim in a little corner not far from the kirk. He opened up his pack and began to cry his wares, with a perennial favourite. ‘Coventry. Coventry thread. Ye will not find a finer, nor a purer blue. For your caps and your cuff work. Your linens your embroideries. Will not run. Will not stain. No blue more true. No counterfeit stuff. Finer than gold. Mistresses, come buy. None is more true blue than Coventry blue.’

He was gratified to find that he had drawn an audience. Not, it was true, so many of the good wives who made up his target group, but several likely lads around the age of twenty, who had sweethearts, doubtless, targets of their own. ‘True blue,’ he appealed to them, ‘to win a leman’s love.’

One of the young men stepped forward. ‘Well met, billie boy,’ he said. ‘Coventry, ye say? What kind a place is that?’ The pedlar could smell the sour ale on his breath.

‘A fine place, my master, where is spun the finest thread.’

‘Aye? Is that a fact? In England, is that place?’ the young man answered, pleasantly.

‘Why, yes sir. At its heart. The very life and heartbeat of that brave green land.’

‘An’ wid ye be, yourself, fae Cuventrie, my friend?’

‘From Warwickshire, sirs. From a place that is not far from it. And I can vouch, upon my life, that you will not find a blue thread of a finer quality.’

The young man grinned at that, turning to his friends. ‘Ur-pon his loife, he says.’

The pedlar, appealing, held out his thread. ‘True blue,’ he tried again. ‘The ladies like it, sirs. An ever welcome gift, and the lady will be yours. I have ribands, too.’

‘Did I hear that right?’ the young man asked his friends. He was not smiling now, but a keen glint in his

eye sent a signal to the pedlar something might be wrong. He took a small step back.

‘Did that rusty bully call my lass a whore?’

‘No, as I assure you, sir,’ the pedlar stammered now. ‘I did not say that.’

‘I doubt he did he say that. I heard him quite distinctly, Tam,’ came back the young man’s friend.

‘I heard the limmar too.’

‘Good masters, what I meant . . .’

But what was meant, or not, was stopped by the flowering of a fist, that burst out into blossom in the pedlar’s mouth.

Above the outer entrance to the St Andrews tolbuith a single glove was pinned. This signified the session of the Court of Dustifute – the pie-powder court, which ruled upon transgressions at the fair, the common law suspended for the day. Convened to that court were the stewards and the bailies appointed to the task, who took their role there seriously. They were chosen from the burgesses and merchants in the town, and chief among them, who spoke now, was a leading beacon in the baxters’ gild.

‘Ye are charged wi’ disturbing the peace of the fair. What do you say?’

The pedlar peered through an eye that was bulbous and closed. His face had swollen up, to a shiny sullen purple, tight as a plum. His answer was muffled by the swelling of a lip, blubber to the touch of his shy protruding tongue. He swallowed on a tooth, a gobbet of slick blood, his answer indistinct.

‘Whit dae ye say?’

‘He says, it was not he that started the affray. That he was set upon.’ The pedlar had a man to speak for him. It was only right and proper that a stranger at the fair should have a countryman of his own to take his part; that was the point of a dustifute court, that none should find himself thrown upon the mercy of a foreign law, without a friend to speak for him. The friend was hard to find. At last, they had pressed into the service a cadger from the south, who had been quick to point out he had not witnessed the assault. He had come reluctantly to support his countryman. Was that not like the English, after all, the baxter sniffed. Cowards, every one.

‘He says that he was set upon. Well then, was he robbed?’

The pedlar had not been robbed. He had still, and plain for all to see, his same pack full of its cheap tricks and toys, his ribands and his laces and his true blue thread. His purse kept the pittance it held when he came with it.

‘This court concludes,’ the baxter said, ‘that ye are guilty of affray, and of disturbing the peace of the fair, and of slander and provokement of a guid man of this place, in that that ye cried his lass a whore, and assaulted him, when he tuik offence at it.’

The pedlar replied to this, in some sort of speech, that the thickness of his accent and the thickness of his lip slobbered to a slur.

‘He says,’ his friend reported, ‘that was not how it was, at all.’

‘Aye, but ye see,’ the baxter leaned across the desk, and looked earnestly into the pedlar’s eye, the one good remaining one, yellow and red, ‘there are fifteen witnesses that swear that it was so, besides those lusty fellows in the vault below; and ye, as I believe, have not one witness that will swear the contrary. Wherefore, you must see, the case is found and proved.’

The pedlar mumbled again, and the baxter found himself irritated by his smoothly stubborn face, bulging like a haemorrhoid. What business did he have in persisting in his obstinacy?

The countryman interpreted, sulking and reluctant, and the baxter found that he was prickled too by the southern cadger’s whining English voice. Why did they think they were never in the wrong?

‘He says that there was a boy, a student from the college, came to wipe his face when he was lying on the ground. A boy with black hair. And, he thinks if enquiries were made in the colleges, that boy might be found, to tell the truth of it.’

‘Absolutely not,’ the baxter said. ‘That maun be a lie, else he was dreaming on the ground. There was no student there. For the very guid reason that, the masters at the colleges prohibit them the fair.’

The last thing he would sanction, in his court, was the risk of an appeal to the university. The collegers he knew would argue black was white. His gild had wrangled hard enough, in troubles in the past, with the man Hew Cullan. And while that man no longer troubled them at large, Giles Locke was as bad. The scholars had no business with the powder court, and the powder court would have none with them.

‘This court finds the charge against you to be proved. And ye will spend the rest of the day, and the night, in the goif stok,’ he said.

The cadger asked, wearily, what that might mean.

‘The pillorie or jougs, whichever one is free,’ a bailie spelled it out.

The southerner shrugged. ‘Then, you will have his death on your hands.’

‘Come, I will not hae that,’ the baxter remonstrated. ‘You will not tell me, cannot tell me, that a man who is fit to tramp the length an’ breadth of Scotland is not fit enough to last a few hours in the goifs or jougs.’ Lily-livered loun, he thought. ‘What age is he, then?’ he considered at last. With a man that was so weathered, it was difficult to tell. Fifty, perhaps? Three score and ten? The man had been a dustifute no doubt for thirty years. And that leathered a man, and made him impervious. Perhaps, after all, a night in the goif stok was not punishment enough, for such a kind of man.

‘How should I know? I do not know him.’ The cadger was surlier now. His part in the process was done. ‘But you can surely see that if you put him in the stocks your bangster bullies’ stones will kill him in an hour. You might as well tie the beggar to the butts, and have them shoot their bows at him.’

There was truth in that. The baxter looked for answer to the other bailies, scratching at his head. They had locked the hot youths in the strong room for a while, to let them cool off. But it was plain that no charge would be levelled against them.

‘We could keep them there, until he serves his time,’ one of them suggested. The baxter disagreed. ‘We cannot do that. Sin they have done no wrong, there would be a riot, see?’

Injustice of that kind would wreak havoc in the town. The powder jurisdiction would vanish in a puff, and its failures would be tested in a higher court. The baxter chose instead a more expedient course. ‘Then he shall pay a fine, and be whipped out from the fair. You shall gang an’ a’.’

‘What have I done?’ the cadger whinnied then. A snivelling sort of man. His kind were all alike.

‘You provoke us, by coming at an unpropitious time, when any decent man would have had the judgement to have kept away. Go, sir. We have been guid to you. Ye shall have an hour, to set upon your path, before we loose the men whom you have so offended, they bay for your blood. Go, and thank us, now.’

The cadger saw his cause was lost, and he was himself complicit in offending them, by no more certain cause than his sorry Englishness.

‘Show up your purse,’ the pedlar was told. And he drew it out, wordless, from under his cloak.

A handful of coins, not amounting to much, that were Scots, and a single English one. The baxter scooped this up. The Scots pennies he tipped back in the purse, and handed it back to the pedlar. ‘Now, on your way.’

He was not a cruel man. And he would not send a pedlar out into a world that was hard on him enough, without the means to prove that he was not a vagabond.

The bailie beside him suspected his softness. ‘Why did ye dae that?’

‘Because we do not want the death of a stranger, here, on our hands. If he will die, let him dae it in a parish far from here.’ His kindness, his softness, must not be suspected. The man could not help it that he was an Englishman. Though he could, and should, have helped his coming here.

‘That is not what I meant. Why did you take the coin that has the English whore on it? That bastard Jezebel?’

The baxter turned over the bright coin in his hand and scrutinised the portrait of the English queen Elizabeth. He was a pragmatist at heart, which made him the perfect judge for the powder court. He was surprised that his friend had to

ask. ‘D’ye not ken? Their money is worth more than ours.’

Part I

Chapter 1

The Queen’s Highway

Tout commencement est difficile

[French proverb, written in the glass at Buxton Hall: Every beginning is hard]

London, July 1586

The house had a stillness Hew mistook for quietude, its inner life in shadow at the close of day. The windows were shut fast against the hum of flies, the vapours of the river bed, swollen after months of rain, swilling to the surface of a heavy heat. He expected, at this hour, to find the family freshened from their evening walk, coming from the cooling air to settle down at cards, the green baize in the parlour cleared of supper things. But the boiled beef platter had been left untouched, the wheaten loaf uncut, the primrose pat of butter melting in its dish. The cards were closed up in their box, the lute lay in its corner, soundless. The Phillips family sat reflective, silent and apart.

‘Mary has miscarried her child,’ Frances said, her slight voice a brittle and strained note of brightness, resonant still in the gloom. Frances had wrapped in a white muslin square a translucent-skinned boy, whose whole she could hold in the palm of her hand, light as a leaf and as perfectly formed, while Mary had turned her small face to the wall, and drawn up her shoulders, narrow and hard.

‘The midwife says she will not have a living child, that there is a fault, deep inside her womb. It cannot be helped,’ Frances said.

Joan Phillips clicked her tongue, distant in the haze like the strumming of a grasshopper. She was vexed at the midwife, at Thomas, her son, who confounded her hopes, at Mary most of all, her fault gaping wide like a cleft in a rock. They had been married for less than a year.

Joan’s husband William looked up from the chiselled oak settle, where he sat brooding and hunched. ‘Thomas must be told. Indeed, he must be told.’

The loss of a grandchild was vexing to him, though Thomas was a boy he found difficult to fathom, secretive and staid. He set himself apart, spelling out his surname in the manner of the French. That Phelippes was a person William did not trust, whose purpose was obscure to him, a sad thing in a son. Children were a blessing, and indeed, a trial, for his daughters were more loving and expansive than his sons, yet their chitter-chat and prattle sometimes frayed his nerves. They had cost him dear enough, in frippery of gowns. If there was one among them, closest to his heart, then it must be Frances, his dead brother’s girl. And that was like his perverseness, Joan would have said. He had brought Frances up to attend to his accounts, and in the careful rows of reckoning that lined his record books, in a neat, narrow hand, lay all that William Phillips wished for in a child. Yet he knew what was right, and proper to be done. The woman upstairs, with her face to the wall, had troubled his conscience. Her fault was a grief to him, in his old age.

Lammas

Lammas Candlemas

Candlemas Hue and Cry

Hue and Cry Martinmas

Martinmas Fate and Fortune

Fate and Fortune 1588 A Calendar of Crime

1588 A Calendar of Crime Time and Tide

Time and Tide Friend & Foe

Friend & Foe Queen & Country

Queen & Country