- Home

- Shirley McKay

Queen & Country Page 3

Queen & Country Read online

Page 3

One trouble had disturbed him in those early days, and robbed him of the pleasure he had found in the deciphering. Among the siege of letters that he dealt with day by day, he had had no word of Giles and Meg. He had asked whether he might write to his family, to tell them he was safe. Laurence had refused.

‘But they will think that I am dead.’

Laurence had answered, ‘Better that way. Then their own lives are not drawn into danger. What they do not know, they cannot hide. They are in the care of Sir Andrew Wood, the coroner. He will have to work to extricate himself, and your family too, from any implication in your escape. It will take him some time to build up credit with the king.

‘Better, for the while, if you are counted dead, until your family has been cleared of all possible suspicion, and the king no longer frets upon these strange events. Your escape must not be linked to Master Secretary Walsingham. Play dead for the while. When it is safe to write, be assured that we shall tell you.’

‘But why should Andrew Wood have risked so much for me, in bringing me to Walsingham? To stop me speaking of his dealings to the king? It were simpler, surely, to have had me killed.’

‘Now that I cannot say. I do not know the man. Perhaps he has a liking for you,’ Laurence had replied.

The question of what force had moved the crownar’s mind came back to Hew, and troubled still. Sometimes, in the night, it would not let him rest.

For all that, he took solace in the work to which he had been set, and the friendship he was shown, at the house in Seething Lane. A day had come at last when he was sent alone, with a letter to be taken to the French Ambassador, to his house at Salisbury Court. That packet, he was certain now, had been of little worth. But the value of it lay in the introduction; the understanding that he was deserving of that trust, in Laurence Tomson’s eyes, was lifting to his heart. He was ready to go out, to be tested in the world.

The first command is patience, Laurence had instructed him. Patience was prerequisite in any kind of spy. But it was not the kind of patience that suffers and endures. It was an endless restlessness, tempered and alert, pricked to wait and watch, alert to any sign. The patience of the cat that fixed upon the mouse-hole watches it for hours, each twitching hair and sinew taut and tightly poised. That kind of patience Phelippes had, that left no pause for doubt.

Chapter 2

Leadenhall

Grey Gelding kept his course, coming into Ware a little after ten, where Hew had resolved to rest for a while, out of the heat of the sun. He entrusted the horse to the ostler at the White Hart Inn to be watered and fed. ‘For he is cold and moist, and serves best in that element. I would keep him cool, and sheltered from the glare.’

At twelve, he took his dinner at the common board. Sixpence at the White Hart bought a satisfying ordinary, of bread and cheese with beef, or mutton in a broth, buttered eggs and beer. He played a game of dice with a group of merchants who were travelling home to Yorkshire, and at their invitation left among their company, safer in a crowd.

Though Grey Gelding was well rested, Hew let him straggle at the tail end of the group. He had no wish to be drawn into a closer confidence. ‘Trust no one,’ Laurence Tomson said. ‘Not you? Nor Thomas Phelippes?’ Hew had teased him once.

‘Anglicus Angelus est cui nunquam credere fas est. Dum tibi dicut ave, tanquam ab hoste cave. The Englishman an angel is, which trusted will deceive thee. Beware of him as of a foe, when he doth say God save thee,’ Laurence had retorted. ‘Phelippes, most of all.’

He could not recall when first he heard the name. He had read it in the letters, carefully endorsed, over and again. Phelippes wrote a small, distinctive hand. Hew came to know the shape of it, familiar as his own, before he met the man. Some while into his stay at Seething Lane, Laurence had produced a page of script in cipher. ‘Cut your teeth on this. The quick is dead and gone, the answer is no longer now of any consequence, but it is knotted tight enough to put you to some exercise. It took Phelippes months to read the Latin script. What your hot brain makes of it, I will wait to see.’

He had worried day and night for a week upon the text, but found that he could make no shape nor sense of it. It was, he saw at once, a simple substitution cipher, play for any child. A schoolboy could have solved it, he concluded furiously. Then he understood.

Phelippes was a Cambridge man, his Latin pure and faultless. While Phelippes was a scholar of the first degree, those Jesuits, who wrote the ciphered text, were not. Their secrets had been framed in a pattern of mistakes, in grammar so contorted, incomplete and villainous, it defied all sense, but the method in its working showed itself to Hew. Alerted to the errors there, he solved it easily.

His courage had been lifted to discover he could read a darkly ciphered script, to hear the very heartbeat of the man who wrote it, and to know his mind.

It was not long after that, in November of that year – 1583, and a vicious winter then – when Walsingham returned, to notice him at last. This notice stilled in him a shiver of excitement, stirred by his success, a surge of foolish pride. He smiled now to recall how supple he had been, how tender to the blade on which he would be whet, how willing to be shaped and put to sharp effect. Sir Francis had not mellowed to him, nor improved in health. His words were brief and brusque, and spoken under cover of a wafting handkerchief, as though he might breathe in some malheur of the Scots, though Laurence had equipped Hew with clean water, soap and shirts. ‘You have been in this house now, how long? Two or three months? Then tis more than time for you to earn your keep. I have found a place for you. Master William Phillips, a merchant in cloth, seeks a privy clerk to assist him with his business at his place at Leadenhall. And also at the custom house.’

In his greenness, Hew had echoed, showing his dismay. ‘I am to be a clerk?’

‘What say you, sir? Too proud? Perhaps,’ Walsingham had pricked him, cruel in his rebuke, ‘you have some other friend, to keep you in that state in which you would be found?’

‘By no means,’ he had answered, ‘should I be so proud. But I had thought . . . I had hoped, that the singular learning to which your honour has put me in the past two months, might have equipped me for a more singular service.’

At that, the man had smiled. ‘And suppose that were the case, would you have expected I should advertise the fact? “This man is Hew Cullan. I have trained him for a spy.” I should not loose you on the world, as an honest clerk, whom no one would suspect?’

Hew had begged his pardon then. ‘I did not understand.’

‘That may be excused. But what I cannot let pass, is that you let your feelings show so plainly in your face. You have much to learn. Consider this a trial. William Phillips is one of the customers for wool in the port of London. In name at least, for in the last years pleading frailty or else by idle negligence, he has farmed his post out to a series of deputies. His deputy reports a strange occurrence in the custom house; an unusual case of fraud.’

The custom house, by common knowledge, was rife with theft and fraud of every shape and kind from the petty to the grand, with the full collusion of the officers who worked there, most of whom were merchants too, and who had little recompense for service to the Crown. It was a tacit understanding of a man in public office, that the office he had paid for, or won by rank and privilege, was his to put to such advantage as could there be found.

‘It is not common,’ Walsingham had said, ‘that the customer himself is heard to make complaint of it. In this most curious case, a theft is taking place under his very nose, and he is baffled by it. Monies are placed in a locked chest, in a strong vault in the custom house. The key to the chest is kept by the collector – or in this case, his deputy – locked in a box. The key to that box is kept by the controller. The box is opened only in presence of them both. Each time they open the chest, the monies inside are diminished. And each of them swears he does not know the cause. The chest has a leak, through which gold runs like sand. Or else there is witchcraft in

volved.’

‘Or else, they are lying,’ Hew had suggested.

‘That, I confess, had occurred to me. Master William Phillips swears it is not so. He requires our help. This riddle of concealment, I shall leave you to detect. Since I have it on authority that you are an expert in resolving mysteries, you shall use your skills to find the matter out. Report to Laurence Tomson what you find.’

As always, Hew was spurred and quickened at the thought of mystery. Doubtless, there was nothing to it but a web of lies. He would soon find out. But his interest in the case was dampened at that time by his fear for the friends of whom he had no word. He had appealed to Walsingham, for any small intelligence.

Walsingham had made a great show of remembering, as though he had the information somewhere in his mind, but could not have expected to have ever had a call for it.

‘Our foothold in Scotland is slidder as glass. The king persists in his affection for the earl of Arran, and despite better counsel, will not be put off from his course. There is stirring against the Protestant ministers. Your friends at the New College are fallen from grace, when it comes to their king, in spite of their faith,’ he had acknowledged at last.

‘But what of my sister, and Giles Locke, her husband?’ Hew had demanded. ‘What news of them?’

Walsingham had answered, wryly, that he did not think their names had occurred in the despatches. ‘As I understand, they are in the compass of Sir Andrew Wood. He is at present building up his credit with the king, which is by no means assured. You should be aware, that the chain which links us to him, and him to your family, is a tangled and delicate one. Were it to be broken, I cannot assure the consequence. You may play your part, by doing as you’re told.’

Hew had understood. The safety of his friends and family rested in a man he neither liked nor trusted. His hopes were held to ransom by the traitor, Andrew Wood. He could not help but say, ‘Sir, I know not what you heard of me, from such as Andrew Wood who care little for their country, but I must tell you that my allegiance is first and foremost to the king of Scotland, and will remain so, though I die for it.’

Walsingham had frowned, but had not seemed displeased. ‘I bear that in mind. But you do Sir Andrew a disservice, when you call him traitor. His allegiance, to speak truth, is not at odds with yours.’

‘He sold you secrets,’ Hew had objected.

‘You may parry words. What you class as secrets, I should call intelligence.’

‘I do not think the king would care to call it that.’

‘Ah, perhaps not. But you will be the first to acknowledge, that particular young man is a poor judge of character. We shall agree on this; while you are here, and under my protection, I shall not ask of you anything that may call into doubt your loyalty to that king. We are careful, too, to see his trust restored in you. Meanwhile, it can do no hurt to place you in the custom house. I have told William Phillips you are an inquisitor, and of some renown. It is worth your while to know, that Thomas Phelippes is his son. For the sake of the engagement, I have told them you are known to him. That is not a lie, for so you shall be, presently.

‘Laurence Tomson tells me that you have made remarkable progress in steganography. When you can compose a cipher of your own, that Phelippes cannot solve, then I will believe it.’

And with those words, that stage was passed; Hew found himself dismissed.

The further north they rode the thicker came the mud that clogged the horses’ hooves and splattered over flanks to stop the roll of carts, the furrowed slough of months of rainfall burying their wheels. As the merchants slowed, Hew drove Grey Gelding on, and in space of half an hour, left them far behind. He was conscious of the loss of progress as the path went on, stony, sparse and narrow as the grey horse tired. He could not gather speed, in darkness or in rain, nor hope to find momentum in the coming days. Therefore he determined to drive on to Caxton, so to steal a march upon the road ahead. For did not forget the purpose of his ride, the leaden hopes and faces left at Leadenhall.

He felt a fond affection for the Phillips family, by force of their simplicity, their failure to collude in the conspiracies around them, to be caught up in intrigues. They had little understanding of the secrets of their son, or the work he did for Walsingham, though they were staunchly proud of it. Only William Phillips sometimes fostered doubts. Once, in failing health, he had confessed to Hew, ‘It would not give me ease, to see Thomas in the custom house. I do not say, you see, that he would not be honest. There are in that place so many more temptations . . . a thousand ways a man can treat to serve himself and not the state. . . . I do not say he would, but he has wit and will, and only God can know what he may choose do with them. He keeps his secrets close. I cannot know his heart. And that, you see, is troubling in a son.’

The house at Leadenhall rang out clear and shrill when all his children came, though that was rare enough. They were brought up in the country, on the Lavenham estate where the second son kept watch upon his sheep, and on the Suffolk cloth men in whose cloths he dealt. A third son travelled for his father’s business over sea, to markets which had shrunk and shrivelled hard in recent times. His letters were read out, a source of news and comfort, though little was divulged in them beyond the price of wool. However slim the thread, his mother spun it deftly, woven into gossip to share out among her friends. The letters were antithesis to those that came to Walsingham, so little were they filled of matter and of worth. And yet beneath the ink was carried on a life, the filtered, fractured figment of an absent son.

William, on the whole, preferred to be in London, wife Joan at his side, and without that brood, to which she seemed to him unreasonably attached. Wherever else he ventured, Frances was the one most often in his company, and the only one he could not do without. In London, she kept house, as well as his accounts, and when the younger children came, she kept them too, as quiet in their place as might be effected, and as well amused.

Together in one bed slept the five youngest sons, and Frances shared a second with the daughters of the house, in a narrow closet next to Joan and William’s own. From the boys’ bedchamber led a ladder to the storeroom in the loft, where a feather mattress had been laid for Hew.

‘It is quiet, at night,’ Frances had said, ‘and at least, warm.’

Packed to the rafters with sheep’s fleece and fells, the loft was close and suffocating in the summer months. In winter, Hew had shivered to the scrabble of the mice, who made their nests and burrows in the pelts, until Frances had extended there the service of the cat, a sleek and savage mouser by the name of Tybalt, beyond his natural manor by the kitchen fire. The plague of mice, receding, was replaced by fleas, for which she brought a candle, in a bowl of water, to be lit at night. ‘They will leap to the light, and be drowned. By no means let it burn close to the wool, or where it may be knocked, or you will start a fire.’

The candle was illicit, and a mark of trust between them, at which he had been touched. By such small acts of kindness, Frances had consoled him through the winter’s bane. And sometimes, lying wakeful in the flicker of that light, a weak and gentle flame, he felt content to lie lapped in the wool, when the wind blew its draught through the rest of the house, or rain drummed at the roof with its close, urgent beat.

It was early in the evening, on a foul November fish day, when he first quit Seething Lane, and was shown in to the parlour of the house at Leadenhall, over and above the busy marketplace. The children had been absent, yet their shadows felt, in every crack and corner of the timbered house, had left him an impression of a well-loved family home. The parlour was cluttered with boxes and baskets spilling out silks and half-finished works, with games of chess and cards, and old and new books that bulged from their spines kippered and split in the blaze from the fire. Countless cushions had been stitched, no folding chair or footstool came without its pillow worked with flower or bird, no shelf without a mantle cloth, no floor without its slippers, poppy red and gold. The walls had been hu

ng with crude Flemish landscapes, painted onto cloths, bought by the dozen at the winter fairs. Though little of it grand, or of the finest sort, it gave the house a pleasing colour, and a homely warmth.

William, Joan and Frances had been settled down to supper of a spinach tart with currants, and a sugar glaze, a confection of a kind they particularly enjoyed, oversweet and perfumed to Hew’s foreign taste. They had received him warmly, with a searching inquisition, and, on William’s part, a faint note of defence. The old man had been cautious, wary still of Walsingham, and Joan unexpectedly keen, in her will to have news of her son.

‘Master Secretary tells me,’ William had informed him, swilling down the spinach with a draught of wine, ‘that you are an expert, in detecting thieves.’

‘I think it very like,’ Joan had suggested, ‘that Scotland is a place that is overrun with villains. For so much have I heard, that there is not a man among them to be trusted. All of them are thieves.’

‘Not all, for certain, aunt,’ Frances had protested.

‘I do not say that Hew here is a villain. Only that, and he a Scotchman, he is well qualified to know one when he sees one.’

‘Such are his credentials,’ William had retorted, who would not have this credit challenged by his wife, ‘and since he has the recommendation of the queen’s own secretary, we take him at his word. He is besides, a friend of Tom’s.’ It was not clear whether he viewed this as an advantage.

‘Now that, I count as strange,’ Joan Phillips had persisted, ‘For I never heard Thomas speak aught of a Scotchman, nor has he been in Scotland, to my best account.’

‘You know that Thomas does not like to speak about his work,’ Frances had defended him. Hew had thanked her for it, secret in his heart.

‘Not to you, perhaps.’

‘Nor, indeed, to you.’ William had observed. ‘He is, for a son, most intricate and secretive. It must be deplored.’

Lammas

Lammas Candlemas

Candlemas Hue and Cry

Hue and Cry Martinmas

Martinmas Fate and Fortune

Fate and Fortune 1588 A Calendar of Crime

1588 A Calendar of Crime Time and Tide

Time and Tide Friend & Foe

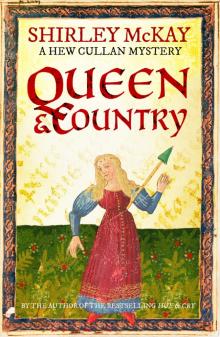

Friend & Foe Queen & Country

Queen & Country