- Home

- Shirley McKay

Fate and Fortune Page 2

Fate and Fortune Read online

Page 2

‘Well, well,’ he said at length. ‘Even these old nags have found their way at last. Take them, Paul, seek out the groom, and I’ll walk on before you to the house.’

The house at Kenly Green had always welcomed him. Coming through the gate he saw the flare of candlelight, the warm and smoky comfort of the hearth. He walked through Meg’s walled garden where the light snow dulled his step and ice congealed the bare, ungiving earth. Below, he knew, the pale shoots sheltered; another month would pass and they would flower. The present sad affair did not unsettle him, for Doctor Locke knew death in all its forms. He walked the brittle earth towards a blaze of light.

But something else had caught his eye that did provoke a frown. In the corner by the wall he saw a figure standing, whiter than the snow, frozen still and desolate as any cast in stone.

‘Hew! My dear friend!’ The doctor’s arms went round him fiercely, clutching with the warmth of his great heart.

Hew Cullan smiled a little foolishly and came to life. The wind laced his cheeks with salt tears. ‘Is it too late, Giles?’ he whispered.

He had come across the sea, and through a white storm, discarding one by one his comforts, horses, friends, through sheets of ice and fog too sheer for ship or horseback, still he came, discarding them, intent upon his coming, through the ice and storm. And now that he was come, he could not enter there, but found himself left stricken in the garden, frozen out, for fear.

‘Oh, my dear friend!’ And the bulk that was the doctor, warming and protecting him, whispered through the tears, ‘Dearest, he died a grand death.’

Prayers for the Dead

They were not mourners, most of them, who came to fill their cups at Matthew Cullan’s funeral. The great hall, with its vast beaming hearth and cluster of candles, closeted and cheered the little crowd. The lure that had attracted them was set out on the board: Lenten salmons green and cured; haddocks fried in butter in sweet herb and caper sauce; coddled eggs in chafing dishes, flummeries and flans. Flanking all were four curd tarts, white and green and blue and yellow, almond, spinach, plum and saffron, coloured like the sun. For drinking there were mellowed ales, or gascon clarets dark as blood, set like jewels in pewter cups. And for those who had ventured in late from the snow, there were fire-breathing waters, syrups and cordials, possets and caudles in great foaming pots. These detested confections were pressed on Hew Cullan, as he was brought shivering in to the hearth. ‘For pity, give him air!’

Hew felt an aching sharper than the pricking of his fingers, waking up too quickly from the numbness of the frost. His sister Meg had hold of his hands, rubbing them briskly, pulling him back from the heat of the flames. ‘He must be warmed more slowly, or the frost will bite.’

The grey dogs napping by the fire had had their fill of fish heads, and forgot their master as they slept. Hew drew in his breath. The air felt hot and raw.

‘We had no hope of you. However did you find a ship?’ he heard his sister ask. The colour had returned into his palms; his fingers stung relentlessly, yet she did not relinquish them. He had crossed the sea from France, on the one ship, the last ship, before the white storm, for week on week through waters vast as winding sheets that billowed upwards to the masts, where he had almost died, yet he could not remember it.

‘I came too late,’ he answered, foolish, inarticulate. From weariness and cold, perhaps from grief, he could not shape the words.

Meg held him close to her, breathing his coldness. ‘We were to bury him today, but the ground is frozen hard, and the beadle has sent word the grave is not prepared. Therefore he must lie another night, and God has willed that you are here to watch him with us. Tis providential, Hew.’

He glanced towards the oak stand bed that occupied a dark place in the room, the heavy curtain drawn. Meg shook her head. ‘He is not there. The wright came in this morning and made fast his kist. We placed it in the laich house, where it’s cool.’

Hew longed for escape from the heat and the crowd. He lit a lantern from the fire, and made his way down to the laich house, the low vaulted cellars below the great hall. The space was a warren of chambers, each large enough to form a separate dwelling place, that served as Matthew’s stores. Hew held the lantern aloft, looking in to each room in turn. The outer vaults were stripped bare, but as he ventured further he found casks of ale and wine and grain sacks, lightly dribbling, where the mice had nipped. Deeper still were bottled fruits and rows of apple racks: last year’s pippins wrapped in paper, wizened and soft to the tooth. The place had a leathery sweetness that brought back his childhood. And in the very centre of the vault, in the room adjoining this, he found his father’s dead-kist, lit head and foot by candlelight. As Hew approached, he heard a low voice singing, and a stranger by the coffin turned and smiled, sketching vaguely with his hand. He did not pause to speak, but disappeared into the apple room. Hew stared after him a moment, before he knelt upon the earth, a little awkwardly, and set down his lamp in the dust. Not since he was the smallest child had he come into his father’s house without asking for his blessing, and he tried to ask it now, but could not find the words. The kist was draped in velvet cloth, the sombre fringe brushed against the dust into a deeper darkness still, beyond the reach of candlelight. Hew fingered the drop of the velvet, committing its touch to his heart. A little mud fell crumbling through his fingers, remnant of the mire of other deaths. But he found nothing of his father there. He was relieved when Meg came down to find him, pressing her hands into his.

‘A man was here praying,’ he confronted her. ‘Was it a priest?’

She would not confess it, even to him. Her eyes opened wide in a gesture of surprise. ‘You know it is not proper to say prayers before the dead.’

‘Aye, and so do you.’ Unexpectedly, he grinned. ‘He always had his way. So too in death.’

Then he whispered, desolate, ‘I thought to ask his blessing, Meg.’

‘You had it, always,’ she consoled him. ‘Will you lift the lid?’

He shook his head. He felt unable to express himself, as though he were still in the garden, frozen out from grief or fear, from neither of those things, but a curious remoteness. Meg was talking still. He forced himself to listen.

‘What matters is that that you are here. The pity is that we did not expect you. The house is full tonight, and I have given up your bed, to Master Richard Cunningham, an advocate. Do you know him, Hew?’

‘I know the name. No matter. I will sleep by the fire in the hall. A blanket will serve well enough.’ Weariness had overcome him. He could barely speak.

‘I cannot think it will,’ she answered doubtfully. ‘All this is yours now. This is your house.’

He stared at her, startled, and cried out in anguish, ‘It cannot be, Meg! Do not say that!’

It was coldness, after all, that affected Hew so strangely, for on his second cup of wine, he began to feel revived, and prepared to face the crowd. Giles Locke was talking with a stranger and Hew’s cousin Robin Flett.

‘What irks me,’ Giles expostulated, through a chunk of cheese, ‘is that ministers reforming of the kirk did not reform the fish days.’

Robin Flett assented. ‘Rather than to divorce the fast from Lent, I hear the parliament is minded to extend it.’

Giles, who was swallowing, spluttered at this, while the stranger laughed. ‘Not this year, I hope. But when you have a wife that cooks as well as yours, the fish days cannot hurt so much.’

‘Aye, that’s true,’ Robin Flett leaned forward and poked Giles in the midriff. ‘For all her flaws, she feeds you well.’

‘What do you mean, her flaws?’ demanded Giles.

‘Well, you know, her flaws,’ Robin waved a hand, a little vaguely, in the air, ‘I do not mean that she has many, save the one she cannot help.’

‘What do you mean?’

The stranger interrupted quickly, catching sight of Hew. ‘Master Cullan, I presume?’

Giles recovered his composure. ‘Hew! Are you tha

wed? Do you know Richard Cunningham? He is a procurator in the Edinburgh courts.’

‘By reputation only, sir.’ Hew addressed the advocate, grateful for the show of tact. ‘I’m glad to see you here.’

Cunningham, Hew judged, was in his early forties; tall and pale-complexioned, sober yet discerning in his dress. His hair was dark, a little grey about the temples, neat and closely cropped. He wore a true black coat, buttoned to the neck with a score of silver buttons, cut in velvet cloth, and his white gloves were slashed at the fingers, showing off his rings.

‘There I have the advantage,’ the advocate observed politely, ‘for I knew you as a child. Your father made me welcome in his house.’

‘I’m afraid I don’t remember. But your name is not unknown to me; nor, I doubt, to anyone who kens the law.’

‘You flatter me.’ The lawyer bowed.

‘Perchance you could do with a lawman, Hew,’ Robin leered unpleasantly. He had been drinking heavily of Matthew Cullan’s wines, and a livid purple smear had spread across his throat. ‘Your father was a rich man, and his legacies are vast. Have you thought how ye might manage them?’

Hew stared at him. ‘I am returned from France this afternoon to find my father dead. Wherefore I confess, I had not turned my mind to it.’

‘Aye, well, ye should. When better than the present, when there’s expert help to hand?’

‘My father’s man of law is based here in the town,’ retorted Hew. ‘When the time is proper to address affairs of business, then I have no doubt that I can call upon his services. I should not presume upon Master Cunningham.’

‘What, say you, yon is too grand?’ his cousin snorted. ‘I’ve yet to meet the lawman who’s o’er grand to grasp at money, and let me tell you, there’s a deal o’ it in sight.’

The advocate ignored this. Mildly, he remarked to Hew, ‘It is the case, I practise from the tolbooth of St Giles, though I do from time to time receive instruction to attend the circuit courts, which is what brings me to Fife. The disposition of wills, and the rest, is, alas, out of my sphere. I have no doubt that your father’s man is sound, for I would ever trust his judgement. Nonetheless, it must be said, my door is always open to you, should there be some service you require.’

‘What did I tell you?’ winked Flett.

‘I am not disposed,’ Hew addressed him coldly, ‘to approach these matters now. But when I do, I full intend to call upon old debts. Tell me, Robin, how’s your ship?’

Robin choked into his cup. ‘Lucy is with child again,’ he changed the subject hurriedly.

Hew raised an eyebrow. ‘Another expense? And so soon?’

‘Not so soon as you think.’ The merchant had recovered. ‘The twins are grown to lusty lads.

‘Have you sons, Master Cunningham?’ he challenged the lawyer. ‘Men must have sons, think you not.’

‘Indeed, I have two, and a daughter, besides. My older boy is placed here at the university, in St Leonard’s college, where I do believe that you were lately regent, Master Cullan.’ Cunningham had turned again to Hew. ‘We were sorry not to find you there.’

‘It’s true, I taught there for a while, to help out a friend,’ Hew answered enigmatically. ‘The college has a new regent, and I understand, another principal, appointed by the king. I’ve heard nought but good of them. How does your boy?’

‘I thank you, well. At first he found the grammar hard, but your father’s secretar, Master Nicholas Colp, was of help to us there.’

‘That man? I would not have him near my sons!’ Flett snorted. ‘I could tell you scandals to disgust you, sir.’

‘No doubt,’ the lawyer said, ‘but I decline to hear them.’

‘What! You balk at scandals! I should think you lawyers thrive on them!’

‘Then you are mistaken, sir. They are the greatest nuisance, for they prejudice the case.’

‘Ah,’ the merchant leaned over and prodded him. ‘But what if they were true?’

The lawyer allowed a faint smile. ‘In court, sir, truth is of no consequence. What matters there is argument.

‘Excuse me. Master Cullan, I believe I see your sister. I must speak with her.’

‘Well,’ the merchant tailed off lamely, ‘as I think I said, tis proper to have sons. Tis high time you gave that wife of yours a child!’ He nudged the doctor. ‘Doctor, heal yourself, I say … but when you come to see us, Hew – Lucy will insist upon it – you will not know my fledglings, fine and fat as any bairns you’ll see. George has four new teeth, and taken quite amiss with it, and Lucy most alarmed, until your good doctor with one of his potions settled it sweetly.’

‘It was Meg’s doing,’ Giles replied brusquely. ‘I had none of it.’ Abruptly, he turned on his heels.

Hew caught up with his friend at the lang board, pouring a goblet of wine.

‘Robin is rude, and the worse in his cups. But you do not usually rise to it,’ he commented.

‘I care nothing for him,’ asserted Giles. ‘Yet he has injured Meg; he calls her flawed.’

‘His wit is dull and pointless; do not let it prick. He means the falling sickness. That was blunt indeed, but not unkindly meant. Her illness is a flaw,’ Hew reasoned gently.

Giles coloured, but conceded, ‘Aye, you may be right. His pinpricks are not worth the flinching. In truth, I am too raw where childbed is the question, for I know the risks. I cannot still my fears. I love her, tis the rub.’

‘What do you mean?’ queried Hew. ‘Is Meg with child?’

Giles shook his head. ‘No, not that.’

‘Then why should you fear? Is she not well?’

The doctor sighed. ‘She is quite well. I do confess, my fear defies good reason. Yet we have been apart some weeks, perforce of your father’s last sickness; and in that time …’ He checked himself hurriedly, ‘Well, it is foolishness. She has been well since Michaelmas, and free from fits, for which we must be thankful.’

He did not seem reassured, but before Hew could probe deeper, he had changed the subject.

‘Well, well, enough of that. How was Paris? Have you found your vocation at last?’

Hew grimaced. ‘I might have had a living there. And yet I could not settle. I was not disposed to stay.’

‘Ah,’ Giles prompted gently, ‘Meg thought you had found a lass.’

‘Did she? Little witch!’ Hew laughed. ‘Aye, I do confess it then. There was a lass. It turned out sour.’

‘I’m sorry for it. These things happen. It was not to be.’

‘In truth, I thought it was. But she construed it differently. She played the coquette, and was true to her kind.’

‘By which I understand you do impugn her race, and not her sex,’ protested Giles, ‘else I should be afraid she broke your heart.’

‘Aye, but for a while,’ Hew answered ruefully, ‘I think she did. No matter, though, tis mended now. But I have done with France, and without my father’s death, I should have come home anyway.’

‘Tis easy to be cozened by the French. They are most inventive in their love. And they can cook, of course,’ reflected Giles.

‘You need not make me out as such a gull,’ his friend objected. ‘I do not doubt the strength of her affections. Only that the pity was, she shared them liberally.’

The doctor patted him ‘Well, well, tis as I said. The girl was French. The loss of that pert temptress is our consolation, since you are come home to us. We’ll find you a Scots lass, sober and constant.’

‘Not yet awhile, I hope!’

‘You might think of it though. You are what, twenty-six? Hew, I hardly like to ask you this, but as your man of physic I presume that I might mention it …’

‘Ah, now that sounds ominous. This will hurt me, I can sense it; don’t put on your doctor’s cap!’

‘I’m serious, though. You say your lass was apt to share her close affections …’

‘Aye, to be more blunt, she spread them thin.’

‘Then she has left you nothing

, I suppose, that should concern you? No boils or pustules, sores? You have been in health these past few months?’

Hew stared at him in astonishment, and then broke out laughing.

‘And I did not know you better, Giles, I should take offence! What then, do you take me for? Colette has wounded nothing but my pride.’

‘Ah, I am glad to hear it. Still, if I examine you, twill only take a moment, and you let down your points. It will set your mind at rest.’

‘It does not need setting at rest. Giles, I am astounded that you ask this at my father’s funeral. I assure you, there is nothing of the sort that should concern you. I am well; Colette was well, and we have not consorted for the past six months. Though wherefore I should tell you this, as doctor, friend or brother – shortly to be none of those, if you pursue this course – is far from clear to me.’

‘Forgive me, Hew, I have forgot myself. In truth, I have forgotten you, which is the worse offence. The fact is I have seen so many cases of the Spanish fleas of late that it has fouled good sense.’

‘Ah, the Spanish fleas! Therein lies your error, for the lass was French.’

‘The Spanish fleas is but a name, tis known here as the verolle or the grandgore, or the Spanish pox; the Spanish call it the Italian disease, the Frenchmen call it espagnol and the English call it French, the morbus gallicus. It Italy they know it as the maladie of Naples, save in Naples where …’ Giles postulated seriously. Then he caught Hew’s smile. ‘You’re teasing me, my friend. It’s good that you are home.’

‘Aye, tis well,’ Hew clapped him on the back. ‘Tis well you take my word on it, and do not bid me draw my pistle at my father’s wake. Let us leave the subject. How is Nicholas?’ Hew remembered his old friend. ‘Is he not here tonight? Why then, is he worse?’

Lammas

Lammas Candlemas

Candlemas Hue and Cry

Hue and Cry Martinmas

Martinmas Fate and Fortune

Fate and Fortune 1588 A Calendar of Crime

1588 A Calendar of Crime Time and Tide

Time and Tide Friend & Foe

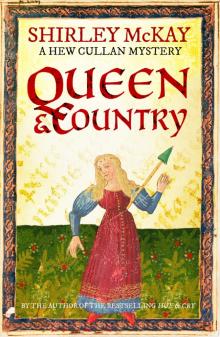

Friend & Foe Queen & Country

Queen & Country