- Home

- Shirley McKay

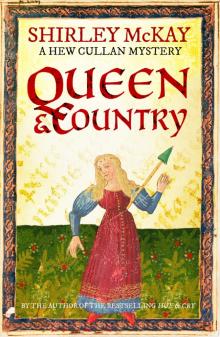

Queen & Country Page 11

Queen & Country Read online

Page 11

An inconvenient truth. The lecture hall smelt wearily of grease and cabbage kale, dispiriting to young and old, tormenting to the wits and to the hollow stomachs of the poorest boys.

‘I know that, sir. Not yet.’

The young man did not bother to reply in Latin; nor did Doctor Locke, for they had come too far, and grown too close for that, this wanton boy’s pale face as troubling as his own. Giles sniffed at the air. He caught a whiff of sulphur he had not smelled before, when the windows had been open to allow the light.

‘There is sulphur, sir, and other things besides. The painter is a subtle kind of alchemist.’

And that alone, sufficient to explain the student’s presence here, his ragged cuffs and fingers, with their yellow stains.

‘Perhaps,’ the student said, ‘you have come here to look at the pictures?’

Giles felt foolish then, to understand how easily the young man read his mind. The student said, ‘There is no shame in it. The drafts are very good. And he has caught the likeness of your spirit and your form. The prentice lad has craft, and skill, and he has caught the essence of you, in a piece of chalk. Your solidness, in fact. His master, I take to be some sort of juglar.’

‘And you,’ observed Giles, ‘are an insolent loun.’ His censure had little effect.

‘Did you know, the prentice lad is deaf as well as dumb? That when his master speaks to him, he does so with his hands? It is a language, quite,’ the student went on, seriously. ‘And I should make a study of it, if I had the chance. The boy reads faces too, as well as the devil reads souls. Have you ever heard it said, that a man’s mouth makes words when his head is cut off? That boy could probably read them.’

Giles retorted, ‘Stuff.’ Pretending to be cross, he was interested in this. He had once read in a book that it was possible to see from the moving of men’s lips, what could not be heard. It was not a common thing, and the ancients did not mention it. He must look it up. But was that not this student’s trick, to try to draw him in? ‘Be that as it may,’ he said, ‘this place is out of bounds. You shall not vex the painters, nor distract them at their work. Go, attend to yours. You might profit from an extra hour or two of study. There is little time enough till your examination. Go to, and apply yourself.’

‘It is hard to find the will,’ the student said, ‘when there is no purpose to it.’

‘I will be the judge,’ said Giles, ‘whether there is purpose to it. You do as you’re telt.’

The student lingered still. ‘Has master Hew come home?’

‘Not yet, to my ken. Be sure that ye will hear it when he does.’ The doctor’s tone was sharper than he felt, whittled on proplexity. His feelings were misread, for the boy said hopelessly, ‘Then I will be gone.’

‘That is by no means certain.’

‘You will tell him what I said?’

‘You must tell him that yourself. I will not give you false hope, though I will counsel as well as I can. But you should know, you must know, Hew is a good man.’

‘As I am not.’

‘Come, do not say that, I will not have that. Go now, to your books, and do not let me find you meddling with the painters.’

‘Very good, professor. Will you come to supper, sir?’ The student had a knack of changing tune precipitate, which Giles found disconcerting. His moods could be mercurial.

‘No. Not tonight. I am going home. And shall go at once, for I must call in on the way to visit the archbishop, who has not been very well.’

‘I can go in your place, if you like,’ the young man suggested. ‘And tell him you were called away, incontinent.’

‘By no means,’ answered Giles. He shooed the boy away, and stole a glance around. The dinner hall was stripped of plate, the stools and trestle tables racked up on one side. On the upper dais where the masters dined, the painter had set out a scene upon a stage, a green-backed chair and table with a pile of books, where Giles had been sitting, artfully arranged, all that afternoon. He had felt an itching, then, to look upon the paper where the boy had drawn, unconscious of the music he was making with his mouth, a stream of squeaks and squawks. The drafts lay on the table, covered with a cloth, but Giles had lost the will to look at them. ‘Vanity, all vanity,’ he muttered to himself. He locked the hall door and lodged the key with the porter, instructing him to lend it only to the painter, and for no other purpose to allow it from his sight.

The comfort of his supper by the fireside had to wait, for the doctor’s journey took him first to the South Street town house of Archbishop Patrick Adamson, who had fallen back into the slurried troughs which plagued him through his life, brought on by drink and gluttony, and politics and posturing. The bishop had returned that morning from the Parliament, and had sunk at once into his old dyspepsia, claiming once again to have been ‘poisoned by a witch’. Giles prescribed, as always, a severe and thorough abstinence, which Adamson, as always, worked hard to resist. ‘I doubt it is a chill I caught upon the road, coupled with the blow of that most dreadful news, has set my bowel a-wammilling. A little aquavite will likely settle this.’

Giles snapped shut his case. ‘Aye then, please yourself. What news was that?’ he asked.

The answer chilled him too, and turned his stomach sour. By the time he set out, on the back of a mare who grew slower each day, the pale moon was masked in a bank of black cloud. It was past eight o’clock by the time that he reached home.

This did not damp down the spirits of his son, who met him at the door, shrieking with excitement, ‘Mine uncle Hew is here! Did I not tell you, he would come today?’

Giles allowed, ‘You did.’ He ruffled the child’s hair. ‘And since you have telt me each day for a fortnight, logic demands it must sometime be true.’

‘He has brought a soldier wi’ him, and he has a wife. The soldier can kill a man, with his bare hands. An’ he will tell to me and to John Kintor how we may do it.’

Giles said, ‘Dear me,’ raising an eyebrow at Meg, who had come in the wake of her wild little son.

‘He brought Robert Lachlan,’ Meg said.

‘That, perhaps, accounts for it.’

‘Robert took Matthew to see to the horses, for a moment only, while I talked to Hew. But it was long enough.’

‘Ah. I see it all.’ Giles surveyed the child. ‘A surfeit of unsteadiness. The bairn has been exagitated to a hurkling heat. Bed is prescribed here, I think.’

Matthew pulled a face. ‘It is not supper yet.’

‘Go with Canny Bett, who will give you supper and a cooling drink. Your uncle will be here still in the morning,’ Meg promised.

‘And his soldier too?’

‘As I fear and trust.’

The child was whisked away, and Giles returned to Meg, cheered by her embrace. ‘Well,’ the doctor said, ‘where is the sorry prodigal?’

‘They have gone to rest, worn out from their journey. Giles . . .’

‘And who is Lachlan’s wife? Can it be that Maude, that went with him to Ghent? For, as I had thought . . .’

‘Whisht, and listen, Giles! The wife belongs to Hew. He met an English lass. Her name is Frances Phillips. She seems the perfect choice. A match for him, I think.’

And that was like Meg, to depend on an instinct. She was not often wrong. But nature sometimes could be cast awry, and instinct blown adrift, by a malignant force. The doctor shook his head. ‘Dearest, though it hurts my heart to be the one to say it, this is not good news.’

Frances lay quite still, watching as he washed. Someone had brought water, scented soap and towels, and a fire was lit, in a little brazier in the centre of the room, distilling the cool air into a soporific smoke. Hew was naked to his waist, moving round the chamber with a settled kind of ease. Folded in the press he found a linen shirt, fresh as the day on which he had left it, interleaved with dried petals and herbs. The scar on his chest shone in the lamplight. Frances had asked, ‘Does this hurt you, still?’ pricking it out with light careful fingers. She

had not seen it before.

On their long journey north, they had not shared a bed. Hew had slept with Robert at his side, while Frances slept apart. So they had escaped the censure of the crowd, and slipped away unseen. ‘She is a chaste piece,’ Robert had said. ‘You will not know where to start with her. It will be like bedding a nun.’ Hew had replied, ‘You should ken.’

The conversation, when it came, was tentative at first, hesitant and shy, for they were strangers still, and began upon it with a strange politeness, civil and reserved. But when they lost their shyness, they had come together deep, and known each other well, and there was meaning to it. Frances had unfolded like a rose and blossomed in his bed. She lay now, quite still, in a flowering of semen and blood, and wondered if that flux was how a child was made, for she had not been told. She remembered Mary, and her withered leaf, the tracery of veins.

Hew was washed and dressed. ‘I hear Giles in the hall. We should go down.’

‘You go on first. I will come after.’

She wanted to stay. In the coolness of the sheets, in the safe milk of his seed, for the rest of her life. ‘I do not want them to know.’

She had the kind of skin that flamed and coloured easily, that bloomed into a blush, upon her breasts and cheeks. He kissed her once again. ‘They will not know,’ he said.

He came into the hall, glowing, from her bed, to find it home again. It was more than home, for Meg and Giles and their small bairns had kindled up the warmth it had when Matthew Cullan was alive, and fuelled it with their own. The hall was furnished with the drapes and hangings Hew remembered from his childhood, his parents’ plate and furniture, burnished to a gleam in the blazing fire. On this winter night, the shutters had been closed and lamps and candles lit, illuminating gloom with confidential light. The board had been set out for supper for four, and a rich jug of claret, fresh from the cask, from which Meg poured a long draught for Hew.

‘Come by the fire. Your travels were long, and the nights here are cold. Too long. Too cold.’ Giles, for all his cares, for all the absent years that had made hard his hopes, could not help but clasp Hew close, and hold him to his heart. ‘Here you are, intact, and back where you belong. God love you, how we missed you, Hew!’

For a moment, in that place, Hew felt overwhelmed. That part of his life, from which he had been snatched, and had come accustomed to have left behind, flooded him with feeling he could barely comprehend, when feeling was a thing he had been taught to hide.

It was Meg who rescued him. ‘Your friend Robert Lachlan asked for bread and cheese. He spent the afternoon drinking with the groom, and has fallen asleep in the library.’

Her brother grinned at her. ‘I will tell him to behave himself.’

‘As I wish you would. Supper will be served, as soon as Frances comes.’

‘She will not be long. Or I will go and fetch her.’

Meg nodded. ‘Anyone can see that she is lovely, Hew. But why did you not tell us that you had a wife?’

‘Because,’ Hew confessed, ‘it came about by chance. I did not know I loved her, till we came to part. We married in great haste, and after I had written to you I was coming home. And somehow, too, a letter did not seem the place, to tell to you the news. I knew that when you met her, you would like her too. The marriage was clandestine. It was, you understand, entirely lawful under English law. Frances is of age, and she knows her mind. But her uncle had intended she should wed another man.’

‘Her uncle?’ queried Meg.

‘She is an orphan, too.’

Nothing in his friend’s account brought peace of mind to Giles. ‘When were you at Berwick, Hew?’ he asked.

‘Ten or twelve days ago. I should tell you, perhaps, that Frances did not travel with me as my wife. I have a friend in the office of the Master Secretary, Laurence Tomson, whose passport allowed me to bring out two servants. I requested the same from the king.’

‘You slipped in on a thread,’ Giles said. ‘For since then, the border has closed.’

Hew asked, ‘Why is that?’ though in his heart he knew.

‘The queen of Scots is dead.’

The words came sharp and cold, with nothing there to blunt or mitigate the force of them. And though Hew had expected it, though he understood a course had been embarked upon which nothing could have stayed, he was shaken to a depth for which he had not been prepared. Giles Locke, as he spoke, was visibly afflicted, which was shocking too, for Giles did not dread death. He was Catholic also, secret in his heart. And Catholics he attended to, in their dying hours, had the best of deaths, however hard they fell, whatever hurt was done to them, because they died in hope.

In the year of plague the dead kists were tipped out, and were filled again; the dead were left to moulder naked in their shrouds. Despite his best beliefs, the ravage of the peste had worn the doctor down. It had left him changed. The magnitude and scale of it was hard to understand. Yet the toll of that flood, counted in drops, insubstantial and small, did not amount to the loss of that queen, whose departure from life had been more than a death; more, to Giles Locke, than its sum.

‘She was killed at the command of the English queen, Elizabeth. Her head was cut off from her neck. This news took a week to come to the king. Patrick says, he marvels at it greatly. Yet I have no doubt he must have expected it.’

‘Once she was convicted, there could be no hope for her,’ Hew said.

The doctor shook his head. ‘Does Frances know,’ he asked, ‘what horror you have brought her to?’

Frances washed and dressed. She had no chest of clothes, no scented smock or shirt, so could do little more than shake her gown for dust, combing out her hair, and tucking it away into a linen cap, as wives were meant to do. Her shoes were worn out to the soles. On the stairway to the hall, she encountered Canny Bett, who put to her a question, and gave her some advice, at which she smiled and nodded, understanding none of it. Her heart was in her mouth as she entered the great hall. She understood at once that there was something wrong. ‘What is the matter, Hew?’

‘Ah, my love,’ he said, ‘I fear the queen is dead.’

Her hand flew to her face.

He realised his mistake, and hers. ‘I do not mean Elizabeth. I mean the queen of Scots.’

Frances cried, ‘Thank God!’ and opened up a gulf between them in that room.

They were good, gentle people, and they did not leave it long, however deep the cracks they plastered over privately. Meg was the first to break into the awkwardness. ‘We must eat. We have a kippil of cunyngs with mustard, and beef in a broth, and a tart, and marchpanes the children have made.’

Frances said, ‘Kippil of . . .?’

‘It means a pair of coneys,’ Hew explained. ‘What the French call, lapin à la moutarde.’ Giles did his best to recover his sangfroid, and came back with a quip, ‘or in other words, cunning as mustard. It is Hew’s favourite, and we are obliged to him, for not coming home on a fish day. Soon it will be Lent, with all the deprivations that entails. In the meantime, we are blessed with a surfeit of fresh meat, and I would call upon you both to help us make the most of it.’

The leprons had kept their sweet delicate flesh, their sauce refined and fragrant, with a subtle heat; the beef had been cooked on the bone, melting with its marrow to a mellow broth, sticky, dark and unctuous. The tart was filled with custard, laced with spice and quivering. There were brittle oatcakes, baked upon a skillet pan, that crumbled in the throat, but also good white bread, that Frances had been told was scarce enough in Scotland. She ate a little of the manchet, dipped in mustard sauce, and a little of the meat, and nibbled at the edge of a sliver of the tart. She sipped at the claret which was deep and dark, and the more of it she drank, she more she felt adrift, floundering in talk. Though Meg was kind in her attentions, and gentle in her speech, the words she used were singular, and hard to understand. Giles had travelled further, and had lived abroad, and had the content of his speech not been convolute and tortuous,

she might have hoped to follow, but she found the language heavy, and the argument abstruse. Even Hew himself, whose gently tempered tones had lulled her from the start, was sometimes falling now into a deeper dialect, and she felt left behind; however long and patiently they broke off to explain to her, she never quite caught up. It was not just the words, but their world that was strange.

They were speaking of the college at the university where Giles Locke was the principal. One of the professors there, a man called Bartie Groat, had perished in the plague.

‘What? Bartie gone?’ Hew wailed.

‘Bartie was the first,’ Giles said. There came on him a weariness, wiping out all energy and weathering to quietness. ‘The peste takes first the faltering, the fragile, frail and old, and sweeps them from its path, careless as the wind. He remained behind when the college was evacuated. Where else should he go? His life was at St Salvator’s. He had decided that his time had come. But you may be assured, Hew, he did not die alone.’

Frances dared not show the pity that she felt; their grief was closed to her. Far across the table, Meg reached for her hand. ‘That was a hard time. The men from the college, who had nowhere else to go, came here to us. We were quarantined, and those who could afford to, fled the town. But Giles did not leave. He remained at the college, tending to the sick, and doing all he could to rein the sickness in, and to stop its spread. It was not long after Martha was born, and we did not see him for almost a year. Paul, who was our servant then, brought letters back and forth, together with supplies, which he left by the wall, not daring to enter the town. And we sent our herbs to them, and waters from the still, to help them where we could. Four hundred people here died in the plague. But were it not for Giles, it could have been four thousand.’

The doctor cleared his throat. ‘Dear me. This a sad thing, to speak of on your first day home. If you will call in at the college, Hew, anytime you will, we can talk of matters, that we do not touch on now. Indeed, I think it best.’

Hew nodded. ‘I can come tomorrow, if you like. For I have in mind to see my man of law.’

Lammas

Lammas Candlemas

Candlemas Hue and Cry

Hue and Cry Martinmas

Martinmas Fate and Fortune

Fate and Fortune 1588 A Calendar of Crime

1588 A Calendar of Crime Time and Tide

Time and Tide Friend & Foe

Friend & Foe Queen & Country

Queen & Country